2020 Winner

Camilla Townsend -

Fifth Sun:

A New History of the Aztecs

A New History of the Aztecs

Biography

Camilla Townsend is Distinguished Professor of History at Rutgers University. She is the author of numerous books, including Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, and The Annals of Native America: How the Nahuas of Colonial Mexico Kept Their History Alive (OUP, 2016), which won multiple prizes, among them the Albert J. Beveridge Award awarded by the American Historical Association. She works in numerous languages, including Spanish and Nahuatl.

Book Summary

In November 1519, Hernando Cortes walked along a causeway leading to the capital of the Aztec kingdom and came face to face with Moctezuma. That story -and the story of what happened afterwards -has been told many times, but always following the narrative offered by the Spaniards. After all,we have been taught, it was the Europeans who held the pens. But the Native Americans were intrigued by the Roman alphabet and, unbeknownst to the newcomers, they used it to write detailed histories in their own language of Nahuatl. Until recently, these sources remained obscure, only partially translated, and rarely consulted by scholars.

For the first time, in Fifth Sun, the history of the Aztecs is offered in all its complexity based solely on the texts written by the indigenous people themselves. Camilla Townsend presents an accessible and humanized depiction of these native Mexicans, rather than seeing them as the exotic, bloody figures of European stereotypes. The conquest, in this work, is neither an apocalyptic moment, nor an origin story launching Mexicans into existence. The Mexica people had a history of their own long before the Europeans arrived and did not simply capitulate to Spanish culture and colonization. Instead, they realigned their political allegiances, accommodated new obligations, adopted new technologies, and endured. This engaging revisionist history of the Aztecs, told through their own words, explores the experience of a once-powerful people facing the trauma of conquest and finding ways to survive, offering an empathetic interpretation for experts and non-specialists alike.

Finalist

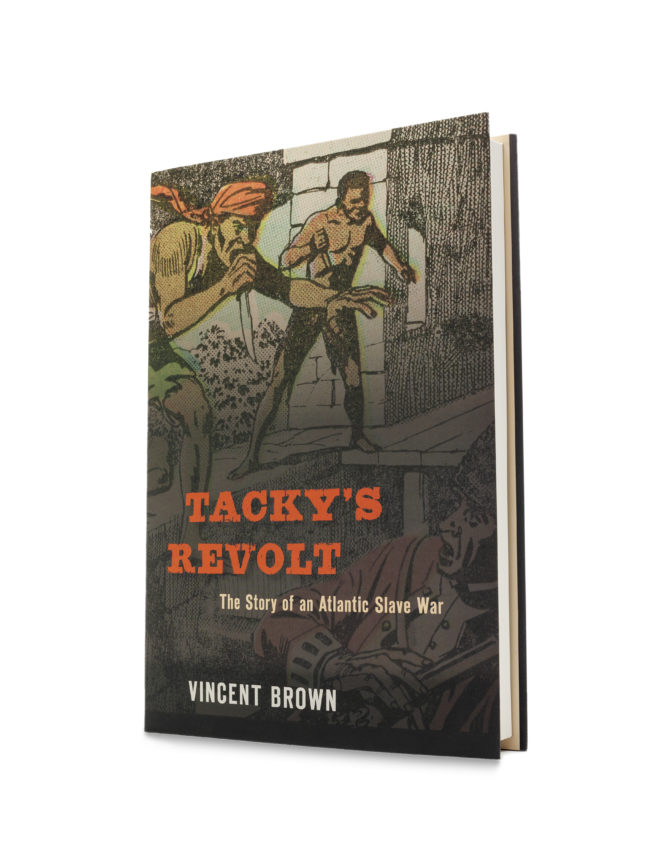

Vincent Brown -

Tacky's Revolt:

The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

Biography

Vincent Brown is the Charles Warren Professor of American History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University and the author of The Reaper’s Garden, winner of the James A. Rawley Prize, the Louis Gottschalk Prize, and the Merle Curti Award. He has received Guggenheim and Mellon New Directions fellowships, and created an online animated map, Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760–1761: A Cartographic Narrative, which has been viewed by 87,000 users in 184 countries. His documentary Herskovits at the Heart of Blackness, broadcast nationally on PBS, won the John E. O’Connor Film Award and was chosen as Best Documentary at the Hollywood Black Film Festival.

Book Summary

In the second half of the eighteenth century, as European imperial conflicts extended the domain of capitalist agriculture, warring African factions fed their captives to the transatlantic slave trade while masters struggled continuously to keep their restive slaves under the yoke. In this contentious atmosphere, a movement of enslaved West Africans in Jamaica (then called Coromantees) organized to throw off that yoke by violence. Their uprising — which became known as Tacky’s Revolt — featured a style of fighting increasingly familiar today: scattered militias opposing great powers, with fighters hard to distinguish from noncombatants. It was also part of a more extended borderless conflict that spread from Africa to the Americas and across the island.

Even after it was put down, the insurgency rumbled throughout the British Empire at a time when slavery seemed the dependable bedrock of its dominion. That certitude would never be the same, nor would the views of black lives, which came to inspire both more fear and more sympathy than before. Tracing the roots, routes, and reverberations of this event across disparate parts of the Atlantic world, Vincent Brownoffers us a superb geopolitical thriller. Tacky’s Revolt expands our understanding of the relationship between European, African, and American history, as it speaks to our understanding of wars of terror today.

Finalist

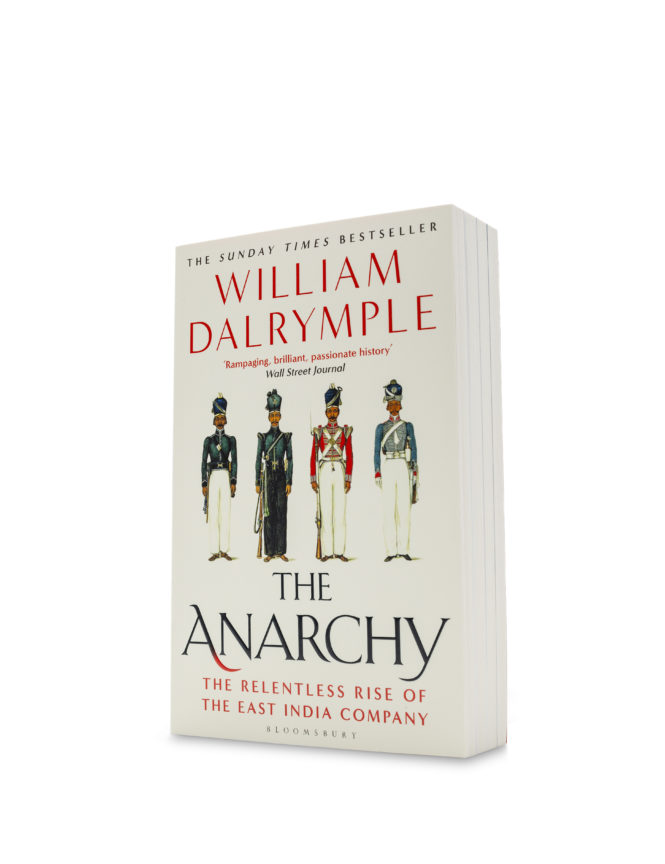

William Dalrymple -

The Anarchy:

The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

Biography

William Dalrymple is one of Britain’s great historians and the bestselling author of the Wolfson Prize-winning White Mughals, The Last Mughal, which won the Duff Cooper Prize, and the Hemingway and Kapuscinski Prize-winning Return of a King. A frequent broadcaster, he has written and presented three television series, one of which won the Grierson Award for Best Documentary Series at BAFTA. He has also won the Thomas Cook Travel Book Award, the Sunday Times Young British Writer of the Year Award, and the Foreign Correspondent of the Year at the FPA Media Awards. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the Royal Asiatic Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and has held visiting fellowships at Princeton and Brown. He writes regularly for the New York Review of Books, the New Yorker and the Guardian. William lives with his wife and three children on a farm outside Delhi.

Book Summary

In August 1765 the East India Company defeated the young Mughal emperor and forced him to establish in his richest provinces a new administration run by English merchants who collected taxes through means of a ruthless private army — what we would now call an act of involuntary privatisation. The East India Company’s founding charter authorised it to ‘wage war’ and it had always used violence to gain its ends. But the creation of this new government marked the moment that the East India Company ceased to be a conventional international trading corporation dealing in silks and spices and became something much more unusual: an aggressive colonial power in the guise of a multinational business. In less than four decades it had trained up a security force of around 200,000 men — twice the size of the British army — and had subdued an entire subcontinent, conquering first Bengal and finally, in 1803, the Mughal capital of Delhi itself. The Company’s reach stretched until almost all of India south of the Himalayas was effectively ruled from a boardroom in London.

The Anarchy tells the remarkable story of how one of the world’s most magnificent empires disintegrated and came to be replaced by a dangerously unregulated private company, based thousands of miles overseas in one small office, five windows wide, and answerable only to its distant shareholders. In his most ambitious and riveting book to date, William Dalrymple tells the story of the East India Company as it has never been told before, unfolding a timely cautionary tale of the first global corporate power.